The pipe that will supply the heat pump, drawing water from the River Rhine in Germany, is so big that you could walk through it, fully upright, I’m told.

“We plan to take 10,000 litres per second,” says Felix Hack, project manager at MVV Environment, an energy company, as he describes the 2m diameter pipes that will suck up river water in Mannheim, and then return it once heat from the water has been harvested.

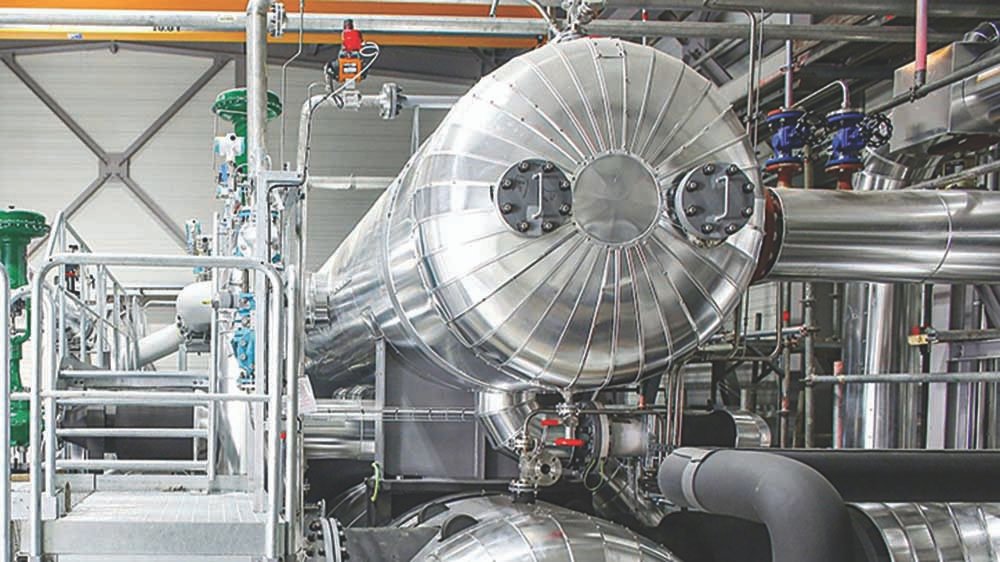

In October, parent firm MVV Energie announced its plan to build what could be the most powerful heat pump modules ever. Two units, each with a capacity of 82.5 megawatts.

That’s enough to supply around 40,000 homes, in total, via a district heating system. MVV Energie aims to build the system on the site of a coal power plant that is converting to cleaner technologies.

The scale of the heat pumps was determined partly by limits on the size of machinery that could be transported through the streets of Mannheim, or potentially via barges along the Rhine. “We’re not sure about that yet,” says Mr Hack. “It might come via the river.”

One person well aware of the project is Alexandre de Rougemont, at Everllence (formerly MAN Energy Solutions), another German company that also makes extremely large heat pumps. “It is a competition, yeah,” he says. “We’re open about it.”

Heat pumps soak up heat from the air, ground or, in these cases, bodies of water. Refrigerants inside the heat pumps evaporate when they are warmed even slightly.

By compressing the refrigerant, you boost that heat further. This same process occurs in heat pumps designed to supply single homes, it just happens on a much larger scale in giant heat pumps that serve entire city districts.

As towns and cities around the world seek to decarbonise, many are deciding to purchase large heat pumps, which can attach to district heating networks.

These networks allow hot water or steam to reach multiple buildings, all connected up with many kilometres of pipe. Ever bigger models of heat pump are emerging to meet demand.

“There was a lot of pressure on us to change the heat generation to new sources, especially renewable sources,” explains Mr Hack as he discusses the decommissioning of coal-fired units at the Mannheim plant. The site is right by the Rhine, already has a hefty electricity grid connection, and is plugged in to the district heating network, so it makes sense to install the heat pumps here, he says.

He notes that the technology is possible partly thanks to the availability of very large compressors in the oil and gas industry – where they are used to compress fossil fuels for storage or transportation, for example. (BBC)

Thursday, March 12, 2026